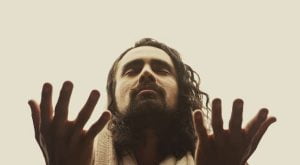

How can we pray like Jesus?

The Sunday lectionary readings for the Sixth Lord's day after Trinity in Year C go on with its progress through Luke'due south gospel, and we achieve Luke 11.ane–13 and Jesus' didactics on prayer. In reading this, we need to be alert to the fact that both the lectionary divisions and the chapter divisions in our Bibles (which are not part of the NT text but were added by Archbishop Stephen Langton in the 13th century) can mislead the states into thinking that each of these sections are isolated units, when in fact they include numerous connections with what has gone earlier.

The Sunday lectionary readings for the Sixth Lord's day after Trinity in Year C go on with its progress through Luke'due south gospel, and we achieve Luke 11.ane–13 and Jesus' didactics on prayer. In reading this, we need to be alert to the fact that both the lectionary divisions and the chapter divisions in our Bibles (which are not part of the NT text but were added by Archbishop Stephen Langton in the 13th century) can mislead the states into thinking that each of these sections are isolated units, when in fact they include numerous connections with what has gone earlier.

The section begins 'And it happened that', in the AV 'And it came to laissez passer that…' and in modern versions 'One twenty-four hours…', all translating the Greek phrase Καὶ ἐγένετο. This is, as we have previously seen, a general statement by Luke locating this at some unspecified point in the model journey that Jesus has embarked on every bit he heads to the climax of his ministry in Jerusalem. He is in a 'sure identify' simply as previously he had approached a 'certain village' (Luke 10.38). And as, in the previous episode, Mary had modelled discipleship by her attention to one thing, which is attending to her one Lord, Jesus now exemplifies this in also being focussed on the 1 in prayer.

But Jesus' attention to his Begetter is not something that he hid from his disciples; instead he showed them and shared with them. It is striking here that the term 'disciple' is non i of mere status or association; Luke is clear that these people are those who are genuinely concerned to larn from Jesus, as the term indicates (mathetesrelated to the cognatemanthano 'to learn'). Following Jesus on the way as well involves existence fix to learn from him and alter as a result.

It appears as though John's distinctive ministry gathered around him a distinctive community, whose particular practices (including fasting 'often', Luke 5.33) set them apart from other groups in get-go-century Judaism, and Jesus' disciples wanted similarly to be distinctive. It is striking that, for Luke, a central distinctive marker was that they should pray, and this becomes a notable theme in his second book. Every bit I take previously noted:

Prayer is a ascendant and recurrent theme, especially in the beginning half of Acts. Prayer or praying is mentioned 33 times in Acts; the majority, 23 occurrences, come in the first one-half and only x feature in the 2nd one-half, of which only six of these actually describe people praying. (Information technology is equally if, having made his point in the first half, Luke stops worrying near reporting prayer in the second half!) Quite often, we are just told that someone prayed, but we are not necessarily toldwhat they prayed—the words they used—whereas in the gospels nosotros are usually told what the words are.

Addressing God as 'father' was not unknown in Judaism, and it has its roots in the Old Testament in verses like

Is he not your Begetter, your Creator, who made you and formed you lot?' (Deut 32.6) and

Only you are our Father, though Abraham does not know us or Israel admit united states; y'all, LORD, are our Father, our Redeemer from of old is your name' (Is 63.16).

But it was not a central feature, and it is absent-minded from the JewishKaddish and the Eighteen Benedictions, which practise have other themes in common with the Lord's prayer, such as the longing for God to establish his kingdom. This distinctive arroyo of Jesus was so notable that Paul continues to refer to information technology, even including Jesus' own Aramaic words of address to God, in Romans 8.15:

The Spirit you received does not make you slaves, and so that you live in fear once more; rather, the Spirit you received brought about your adoption to sonship. And by him we weep, "Abba, Father."

The close association here between the address of God as Father and the work of the Holy Spirit has already been expressed in the previous chapter. Jesus, 'full of joy through the Holy Spirit' (Luke x.21) addresses God as Father, and rejoices in God's revelation of himself. Specifically, we can simply know him as father through divine revelation; it is not something we can merely work out for ourselves.

Luke also explicitly connects the work of the Spirit with the coming of the kingdom of God. This has already been anticipated in the words of Simeon in Luke 2.25–32, where the Spirit has revealed to him the hope of the restoration of Israel in the person of Jesus. And information technology is picked up at the showtime of Acts, where the disciples question nigh the kingdom (Acts 1.6) is answered with the promise of the sending of the Spirit (Acts 1.8). Thus the themes of the fatherhood of God, the coming of the kingdom, and the piece of work of the Spirit are inextricably linked. The Spirit brings the presence of the kingdom in which we are adopted as children of our heavenly Father.

If the fatherhood of God was a modest theme in Judaism, the question of the nature of fatherhood loomed large in the Roman imperial context of Luke's audience. The father of the household's main quality was that of having accented dominance over the members of the household, including in some circumstances the power over life and death. It was the father who decided whether a new-born should be kept or abased to exposure. By contrast, Luke portrays God as a father who is total of compassion and mercy.

The poetic course of the prayer still has the fundamental structural elements of the longer version in Matt half-dozen; the ii petitions have the same pattern of four words equally the three petitions in the longer version, and thus tie the honouring of God's proper noun with the coming of God's kingdom. When we treat 'Hallowed by your name' as an extension of our address to God, we miss the indicate; 'May your name be honoured' functions equally a parallel to 'May your kingdom come, [may your will be done].'

The sense of anticipation of the coming kingdom is something that has marked the early chapters of Luke, with numerous characters full of expectation of the new matter God is nigh to exercise amongst his people. They are non, however, portrayed as passive observers, but active participants getting themselves set up for this new affair. Nosotros should therefore see Luke as understanding that these first petitions require our action likewise every bit our expectation; nosotros laurels God ourselves, and nosotros participate in the work of the Spirit which marks the presence of the kingdom in our midst (Luke 11.20), only as we actively participate in the kingdom dynamic of the giving and receiving of forgiveness.

In Luke, 'testing' (πειρασμός) is associated consistently with opposition and the pressure that results from faithful discipleship; this prayer becomes peculiarly pertinent in the opposition that is experienced throughout Acts.

Whereas in Matthew, Jesus' teaching nearly the Lord's Prayer finds its place in Jesus' teaching nigh other aspects of personal discipline, Luke here links it with further instruction on asking God for things. The two stories that follow (asking a neighbor for bread, and a son'southward request to his father) are clearly linked to the instruction on the Lord'due south prayer—the start through the repetition of the term 'staff of life', the second through the link with the language of fatherhood, and both through the repetition of 'asking' every bit a virtual synonym for 'prayer'.

Both episodes brand use of the principle of 'how much more', the beginning implicitly, and the 2nd explicitly. The motif of friendship (indicated by the fourfold repetition of the term 'friend' in the showtime story) is an idea non discussed in Judaism, simply prominent in fence amongst pagan philosophers. Friends can be superior, inferior, or equal, but they are leap together past concepts of honour and obligation. Friends will, because of honour, reluctantly be obliged to assist a neighbor—how much more volition our generous Father in heaven respond to our request. Luke's depiction of the story is quite ordinary and practical, and assumes the realities of everyday life: three loaves is what is needed for a modest meal and has no symbolic significance; the friend mentions that he 'and my children' are asleep, reflecting the usual first-century state of affairs of a family living together in a single room (compare Luke eight.sixteen 'a lite on a stand is seen past all who enter a firm'); and the neighbor is close by in a context where these minor, one-room houses are built cheek by jowl side by side to one some other. Again, there is no particular symbolic significance to the egg and the scorpion, despite both speculation and postulations about textual revision; eggs are a common part of the diet, and scorpions common in that function of the earth, every bit I once plant when camping on a beach in the open air and discovered a small scorpion in my sleeping bag.

If the concern in starting time response to the disciples' question is the 'technology of prayer' ('what should nosotros say?'), the business in the second half shifts decisively the the graphic symbol of God ('to whom do we pray?'). What matters above all is agreement the nature of the ane to whom nosotros pray—a loving and concerned father, not a sleeping and indifferent god, 1 who is concerned with our needs, and is more than willing to pour out his Spirit upon us.

We are urged to pray, since Jesus is the model pray-er, our Father is a loving responder to our prayer, the Spirit is poured out to help and empower us; because to be a disciple is to exist one who follows and learns from Jesus' example 'on the way', and because nosotros long, like all other disciples, to see God's kingdom come, both realised now in our earth and in the future when Jesus returns.

If you enjoyed this, do share it on social media, perhaps using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo.Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you lot have valued this mail, would you lot consideraltruistic £1.20 a month to support the product of this web log?

If you enjoyed this, do share information technology on social media (Facebook or Twitter) using the buttons on the left. Follow me on Twitter @psephizo. Similar my page on Facebook.

Much of my work is done on a freelance basis. If you have valued this mail, you can brand a single or repeat donation through PayPal:

Comments policy: Practiced comments that appoint with the content of the post, and share in respectful debate, can add existent value. Seek offset to understand, and then to be understood. Brand the most charitable construal of the views of others and seek to larn from their perspectives. Don't view debate as a conflict to win; address the argument rather than tackling the person.

Source: https://www.psephizo.com/biblical-studies/how-can-we-pray-like-jesus/

Belum ada Komentar untuk "How can we pray like Jesus?"

Posting Komentar